Although devloped countries were the main architects of the BIT universe, some treaty features have a distinctly developing country handwriting as our analysis of African BIT innovators suggests.

Although devloped countries were the main architects of the BIT universe, some treaty features have a distinctly developing country handwriting as our analysis of African BIT innovators suggests.

Picture: Paul Keller, Innovation Advertising, Flickr

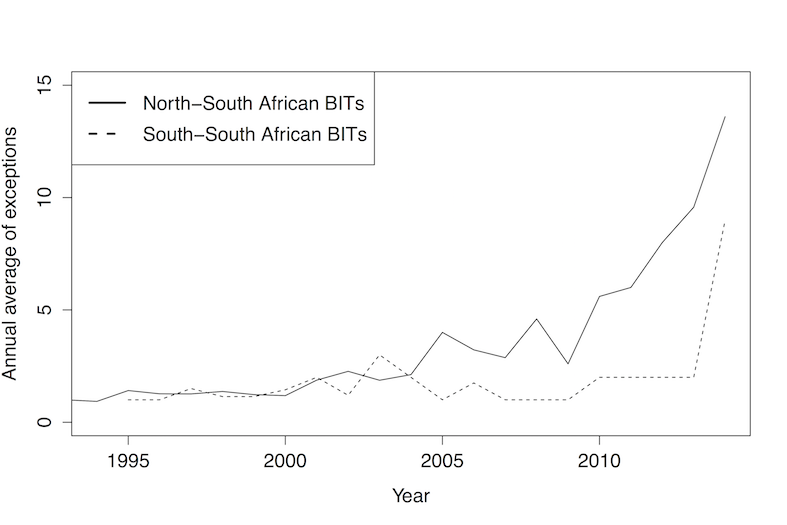

Today treaty design innovation is often associated with American investment treaty practice. Yet, the true innovators at the turn of the century were developing countries, including in Africa. In the late 1990s and early 2000s - well before international investment arbitration became widely known - Mauritius, Uganda, Burundi or Botswana routinely inserted general public policy exceptions into their bilateral investment treaties (BITs). Since then, however, African countries have turned from innovators into imitators. Indigenous policy space provisions in South-South Agreements are being abandoned while most innovation is imported from developed countries via North-South investment treaties. A new research paper explores these treaty dynamics in Africa identifying rule-makers and rule-takers.

In 1985, a new public policy exception emerged in the China-Singapore BIT. Article 11 entitled “Prohibitions and Restrictions” read:

The provisions of this Agreement shall not in any way limit the right of either Contracting Party to apply prohibitions or restrictions of any kind or take any other action which is directed to the protection or its essential security interests, or to the protection of public health or the prevention of diseases and pests in animals or plants or the protection of its environment.

Not only was the clause the first general public policy exception of its kind, but it was also special for two additional reasons.

First, it provided more regulatory space to protect non-economic values than alternative provisions included in later BITs signed by developed countries. The latter are typically modelled on GATT Article XX. Public policy regulations subject to a GATT XX exception have to pass a necessity threshold and meet a good faith and non-discrimination test as part of the clause’s chapeau. The “Prohibitions and Restrictions” clause, in contrast, requires no similar conditions making it easier to invoke (and potentially also easier to abuse).

Second, and perhaps more importantly, the clause is a policy space exception indigenous to the South - a rare creature in a BIT universe shaped mostly by Northern templates. It has never been systematically included in BITs of developed countries. In contrast, after its inception in the China-Singapore BIT in 1985, it spread throughout the Southern hemisphere as the network graph below highlights (comparing it with GATT XX type clauses that are country-specific rather than common to entire regions).

The figure is a network graph that connects two exception provisions if they are textually similar to at least 50%. While most clusters that emerge belong to the network of individual countries, one cluster consists of a clause that is common to several treaty networks as our color coding highlights - the “Prohibitions and Restrictions” clause. The provision thus diffused not only within but also across countries.

In the 1990s, “Prohibitions and Restrictions” clauses made their way via Mauritius into the BITs of continental African countries. More than a dozen Mauritian treaties, but also the Eritrea-Uganda BIT (2001) in Article 14, the Burundi-Comoros BIT (2001) in Article 12 or the Botswana-Egypt BIT (2003) in Article 12 for example provide for such a clause. During the same period Botswana additionally introduced an environmental measures provision in Article 13 of the Botswana-Egypt BIT (2003) and Article 12 of the Botswana-Mauritius BIT (2005) reaffirming commitments under international environmental agreements - well before similar clauses were first integrated into Belgian treaty practice where they are now frequent. Hence, at the turn of the century, African countries were at the forefront of global efforts to balance public interest regulation and investment protection.

Since then, however, Africa has turned from innovator to imitator. A review of recent African BITs suggests that most of its public policy exceptions are imported. Developed countries, after being exposed to symmetrical investment flows and arbitration claims have included policy exceptions into their own model agreements. Today African countries that sign BITs with Canada, the United States or Japan are the champions of policy space as they import innovative exceptions from the North. While this is good news for their regulatory flexibility, it is bad news for the role of African countries as rule-makers and innovators. Home-grown treaty language remains a more tailored means to safeguard the policy space necessary to balance investment protection and non-investment values in Africa. Efforts to conclude a trans-African investment agreement may thus be an opportunity to revert back from the role of imitator to that of innovator.

When official treaty negotiations end, unofficial negotiations begin. Changes made during “legal scrubbing” can turn the original deal on its head as our text-as-data analysis shows.

When official treaty negotiations end, unofficial negotiations begin. Changes made during “legal scrubbing” can turn the original deal on its head as our text-as-data analysis shows.