While all attention is focused on mega-regional negotiations, European states are quietly beginning to redesign their national investment treaty programs. The recent Slovakia-Iran BIT gives a taste of the innovations to come.

While all attention is focused on mega-regional negotiations, European states are quietly beginning to redesign their national investment treaty programs. The recent Slovakia-Iran BIT gives a taste of the innovations to come.

A new wave of European treaty negotiations?

When the Lisbon treaty shifted competency for foreign direct investment from EU member states to the EU Commission in 2009 it provided an opportunity for Europe to update its investment policy. After fifty years in which European states had made little substantive changes to their investment treaties, the EU Commission seized the occasion to radically depart from the traditional short and simple European treaty model and introduced far reaching substantive refinements and procedural reforms, among which is the creation of an investment court system, in its free trade agreements (FTAs) with Canada, Vietnam and Singapore. Today, however, these deals are embroiled in legal and political challenges. While these EU-led agreements fight an uphill ratification battle with uncertain outcome, the responsibility for updating Europe’s investment policy is beginning to revert back to EU member states, many of which have quietly begun to reboot their investment treaty programs.

Under an interim arrangement adopted in 2012, the EU allows its member states to continue to negotiate (or renegotiate) investment treaties with countries with whom the EU is not currently engaged in investment treaty talks. Such negotiations have to be notified to the EU and their outcome is subject to the Commission approval. Up to now, only a handful of treaties have been signed under this arrangement. Yet with progress on EU-led FTAs stalled, member states are more likely to make use of this procedure. In addition, some EU members are beginning to think about renegotiating their existing treaties to align their outdated agreements with today’s policy preferences and the EU template. Following the slow-down in BIT negotiations in recent years, we are thus likely to see a new wave of European BITs in the future.

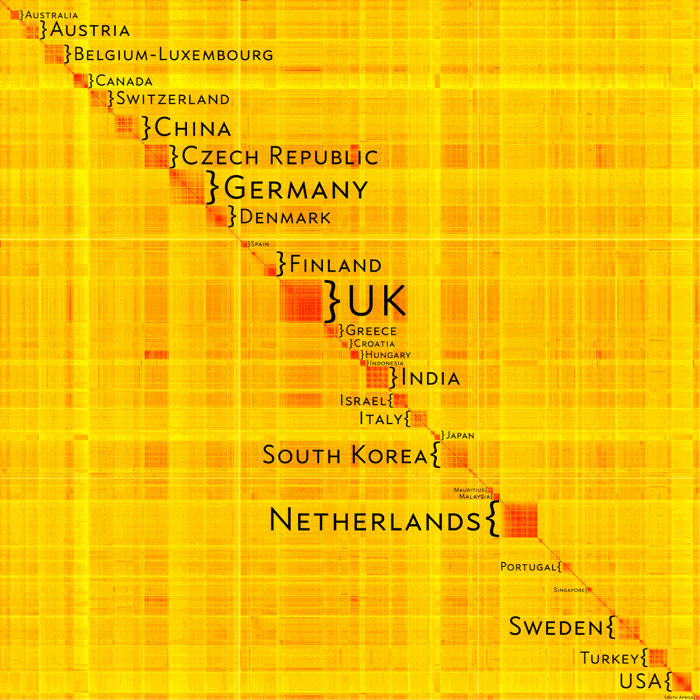

The other major development reverting focus from the EU Commission back to EU member state is of course Brexit. Upon leaving the EU, Great Britain will have to define the investment policy it wants to pursue in future FTAs and BITs. The new government has big shoes to fill: the network of UK BITs is the most consistent in the world. UK treaties textually overlap with each other to more than 70% on average, which is higher than for any other country. Given that the UK network comprises more than one hundred treaties concluded over 35 years this consistency is a remarkable feat. Safeguarding that heritage while setting the terms for Britain’s future investment policy will be challenging.

Slovakia-Iran: A BIT 2.0

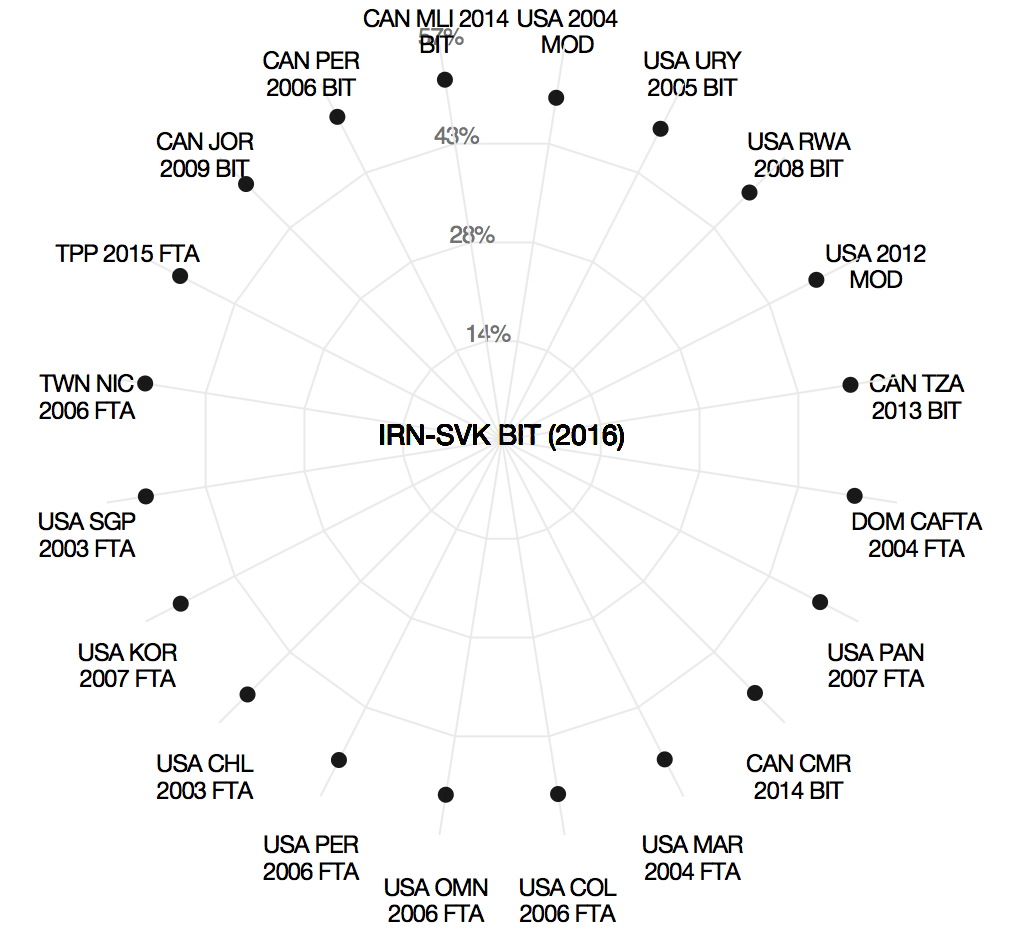

So what are we to expect from European states as they reboot their investment treaty programs? A taste of the things to come is the Slovakia-Iran BIT signed earlier this year. The BIT is a radical departure from both Slovakia’s and Iran’s prior practice. IAReporter provides an excellent overview of the treaty’s novel features and suggests that Slovakia is the source behind these innovations given that Iran has recently signed more conservative agreements. Our text-as-data tools can shed further light on how novel this new BIT really is and helps us identify from where its authors drew inspiration. This analysis yields several surprises.

First, the BIT is radically different from both prior Slovak and Iranian practice. On balance, however, it leans closer to the former. While several Slovak treaties are textually related to the new BIT on at least some provisions, Iranian treaties do not feature on our list of its 20 textually closest neighbor treaties. This lends some evidence to the claim that Slovakia and not Iran is chiefly responsible for the treaty’s design.

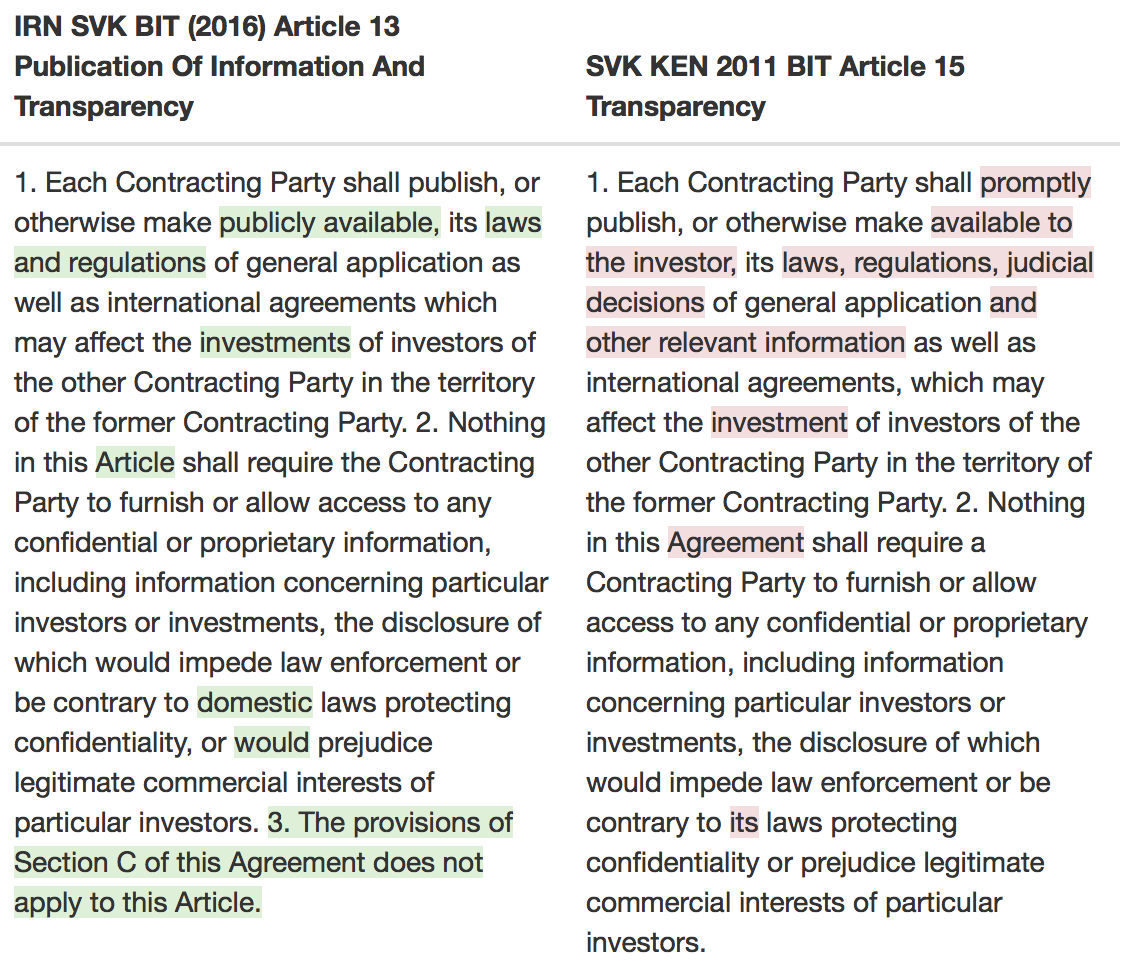

Article 15 of Slovakia-Kenya BIT (2013) is most textually similar to Art. 13 of Slovakia-Iran BIT (2016)

Second, while one may have expected Slovakia to follow the EU Commission’s lead in redesigning its agreements, this is not the case. Surprisingly, the Slovak-Iran BIT instead corresponds most closely to the 2004 U.S. model BIT with a textual overlap of 51%.

Finally, the BIT seems to have been inspired by an impressive potpourri of different agreements. Article 3 on the standard of treatment, which includes fair and equitable treatment (FET) and full protection and security, is most closely related to CETA’s, but excludes some of the latter’s features such as the extendibility of the list of FET violating conduct or the admissibility of the investor’s legitimate expectations. Article 11 on general exceptions partially mirrors Article 10 of the Canada-Jordan BIT (2010). Article 20 on claims manifestly without merit relies on the language from the Australia-Chile FTA (2009) Investment Chapter Article 10.20.

The Slovakia-Iran BIT thus presents a new type of agreement – a BIT 2.0 so to speak. It does not merely refine the prior treaty practice of the signatories. Nor does it unconditionally subscribe to EU thought leadership. Instead, it creates a new treaty template from scratch bearing little resemblance to any other treaty we have seen in the investment law universe. While it draws from recent BITs or investment chapters from a variety of countries, it also adapts them to its own needs creating a unique and tailor-made agreement. Indeed, as IAReporter notes, some of the new inclusions seem specific reactions to Slovakia’s unique experience as a respondent in investment arbitration. It, for instance, carves out public health insurances from the treaty’s scope after having faced multiple investment claims on the issue.

The Slovakia-Iran BIT thus indicates that exciting times lie ahead. If other European countries follow suit, we may see the emergence of a new generation of negotiated and re-negotiated agreements that draw from best practice while tailoring it to new needs.

Our interactive website allows for an in-depth assessment of the Slovakia-Iran BIT.

GUEST POST by

GUEST POST by